Survey on Illegal Ivory Trade of China-Myanmar Border: Our Covert Photographs Revealing Reasons Behind the Disappearance of Elephants

In July 2018, GEI visited numerous ports on the border between Yunnan, China and Myanmar. We paid visits to jewelry, antique, bird and flower markets as well as souvenir shops. These trips, however, were not part of a summer vacation, but aimed to investigate the illegality of the China-Myanmar border ivory trade issues.

This survey is part of the evaluation on illegal ivory trade to better understand the implementation of the China’s ban on domestic ivory trade since its enactment on December 31, 2017. Due to international concerns of the spillover effect of China’s ivory ban on the market in neighboring countries such as Myanmar and Laos, the border between Yunnan and Myanmar was selected as the first site to be surveyed. The survey will contribute to understanding in two aspects: first, it will investigate if there is a smuggling of ivory into the domestic market, and second, seeks to confirm whether or not the above concern is actually happening.

In addition to investigating the smuggling of ivory products in the market, GEI also visited officers from local forestry departments, customs, and forest police in several border cities to learn about the measures they have taken to combat illegal ivory and other wildlife trade.

Image Source: GEI

China leads the way for global elephant conservation

China is one of the most prominent ivory markets in the world. A few years ago, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, the world’s leading author of African elephants, was asked a critical question: “What is the biggest challenge global elephant conservation faces in the 21st century?” His answer was, and still remains, ‘China, China, China…”. Because of high demand for ivory, the number of African elephants has decreased from 1.3 million in the 1970s to 600,000 after ten years. At the end of 2016, the number of African elephants was a mere 350,000.

Over the years, thousands of patrol officers at African national park reserves have been killed in attempts to protect elephants. The number of deaths of foreign aid workers in the area is even more staggering. Nearly every year, we hear news about people getting killed over the protection of elephants.

One of Kenya’s largest big-tuskers, Satao, was killed by ivory poachers. His entire face, along with ivory tusks, was cut off. Image Source: Tsavo Trust

The atrocities of the ivory market and pressure from international public opinion forced China to take a difficult, but world-renowned step in 2017:

On December 31, 2017, China officially passed the “Ivory Trade Ban,” prohibiting domestic ivory trade entirely, and completely stopping the commercial processing and sales of ivory and ivory products.

Ivory confiscated in Zhuhai, 2016. Image Source: New York Times

Cross-border illegal ivory trade has become the next focus

However, the huge profits backing the ivory trade make it apparent that the industry will not easily disappear. Some experts believe that the closure of the legal ivory market in China may lead to the market being transferred to other countries, with the China-Myanmar border as one of the hotspots.

The area bordering China and Myanmar has always been a “troubled place,” and it currently hosts one of the most active areas for illegal wildlife trade. Due to political turmoil in the border regions of Myanmar, especially between armed forces of various ethnic minority groups and the Burmese army, the laws and regulations on wildlife protection in the central government of Myanmar cannot be implemented in border areas. Although the ethnic minority groups in the region have relevant regulations, there are no strict methods of enforcement. Thus, illegal wildlife trade in border areas is generally uncontrolled. Not only are locally poached wild animal products being sold here, but illegal products from Africa and other Southeast Asian countries are also traded here.

Image Source: National Public Radio

Border research confirms the views of experts

In conducting this survey, the most shocking finding was witnessing the illegal wildlife trade in the markets and shops near the port of Mong La in Myanmar.

Mong La, the capital of Special Region No.4, is located opposite to the Chinese town of Daluo in the Yunnan province. It is now controlled by the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), holding a high degree of autonomous governance.

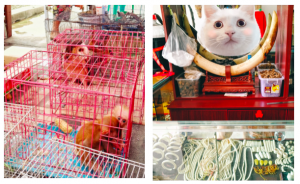

The local farmers market, surrounded by shops selling ivory products and other endangered animal products, can be found on the less-than-ten-minute drive from the Daluo port to Mong La. A large number of these “specialty stores” carry ivory ornaments and other ivory products. The endangered animal products sold include tiger bones, rhinoceros horns, pangolins, Burmese mountain turtles, helmeted hornbill skulls, hawks, and monkeys. From the day of GEI’s visit, it appears the local sales of endangered animals are under no supervision, and businesses are not worried about being penalized for law violations. Most merchants do not allow photos, which leads us to speculate that exposure of these markets will lead to increased supervision.

Image Source: GEI

The difference in problems between China and Mong La

Judging from the results of the survey, the illegal ivory trade markets in China and Myanmar have great differences.

In China, the illegal ivory market has been well controlled. The ivory market has been largely reduced, with the price of ivory significantly devaluing since 2017.

GEI found several shops in the border city of Yunnan selling suspected ivory products. Most of these shops displayed one or two suspected ivory bracelets on the counter. When GEI acted as a potential buyer, the merchants proceeded to take more ivory products out from behind the counter. Upon further inquiry, the merchants would say something along the lines of, “We aren’t allowed to sell ivory anymore, so we have our private collections. If you’d like to purchase, I’ll sell to you.” This exemplifies China’s ban on ivory trade coming into force, with such policies being backed up by law enforcement.

Obviously, we believe in the strict enforcement of the ivory trade bans and it is apparent that smugglers have continued to supply merchants with illegal ivory sources. Through WeChat communication with some merchants, we also found a multitude of online ivory transactions. These online transactions lack tracking methods, allowing merchants to finesse around allegations of illegal trade and avoid source exposure. Additionally, survey results yielded information that shops sold mammoth as well as elephant ivory to tourists. This shows that, to a certain extent, the ivory ban can be used by merchants to entice guests with the rarity of their products, allowing the buyer to think they are obtaining exotic, rare goods.

Image Source: GEI

GEI will continue to help promote bilateral policy and law enforcement cooperation to combat cross-border illegal ivory trade

This survey gave us a clear understanding of the illegal ivory trade on the Yunnan border. We will continue our research and conduct similar surveys on borders and port regions to improve policy evaluation and propose relevant corresponding policy recommendations.

In response to domestic ivory markets being transferred into neighboring countries, GEI will help promote policy exchanges and cooperation between China and neighboring countries as a joint effort to combat cross-border illegal ivory trade.

In conducting this survey and seeing such a large volume of ivory products still being sold, we must make the conscious effort to constantly remind ourselves: There is still a long way to go to protect the elephants.